|

16/5/14

|   | ||

http://sangam.org/2011/10/

Arular Arudpragasam, Sri Lanka Guardian,

Arular Arudpragasam, Sri Lanka Guardian,

August 18, 2009

The British Demarcation of the Tamil Homeland

Towards a Peaceful, Equitable and Sustainable Sri Lanka

Part 6

by Arular Arudpragasam, Sri Lanka Guardian, August 18, 2009

With the other Tamil Province (Northern Province), the Eastern Province shares the honour of being the richest timber producing portion of the Island.- Ceylon Manual 1910: Page 313...

The Sinhalese & the Tamil districts - Ceylon is also divided into the Sinhalese district and the Tamil district. The former comprises the Western, Southern, Central, North-Western and North Central Provinces, with Uva and Sabragamuwa and the latter the Northern and Eastern Provinces. In the former the Sinhalese race and language predominate, and in the latter the Tamil. - Ceylon Manual - 1908 - Page 34. |

(August 18, Geneva, Sri Lanka Guardian) The British inheritance of the Dutch possessions of Ceylon which was mainly an incident of political exigencies that took place in Europe and the transfer of power was more of a political process than military conquest. In the beginning the English, like the Dutch before them, adopted a friendly attitude to the Kandyan Kingdom. The military operation of the British forces to take over the Dutch possessions of the North East started on the 18th August 1795 by taking Trincomalee, followed by Batticaloa, Point Pedro, Jaffna and Mannar, and was complete by the end of the year.

(August 18, Geneva, Sri Lanka Guardian) The British inheritance of the Dutch possessions of Ceylon which was mainly an incident of political exigencies that took place in Europe and the transfer of power was more of a political process than military conquest. In the beginning the English, like the Dutch before them, adopted a friendly attitude to the Kandyan Kingdom. The military operation of the British forces to take over the Dutch possessions of the North East started on the 18th August 1795 by taking Trincomalee, followed by Batticaloa, Point Pedro, Jaffna and Mannar, and was complete by the end of the year.The initial administration of the maritime areas by the officials from Madras administration, marred by administrative ignominy and corruption, soon brought the Maritime areas into a state of revolt.

The Madras administration came to an end and the Maritime areas became a crown colony to be ruled from London in 1802 and a Governor was appointed by the British Crown. The Governor reverted to the system adopted by the Dutch which was closely aligned to the native authority structures and divisions of earlier times.

The maritime divisions now called collectorates as in India, were divided into Colombo. Kalutara, Galle, Matara, Magampattu, Chilow, Batticoloa, Trincomalee, Vanni, Jaffna and Mannar.

Soon a slow evolutionary programme was set in motion based on the ingenuity of the British officers who took great interest in local conditions.

Subsequently collectorates were abolished, and were divided into 13 Provinces including those of Jaffna, Mullaitivu, Trincomalee, Batticaloa and Mannar.

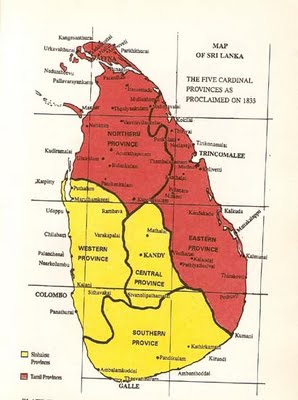

The Formation of the Five Cardinal Provinces During the Early British period.

Since the decision of the British to fuse the political divisions of the Island into a unitary state under the British Crown, the British colonial rulers have attempted to recognise the existence of the earlier political divisions in various ways. The recognition and accommodation of the existing political divisions has remained important in determining the unit of administration at lower levels since such divisions are distinguished by factors of uniformity that permits rationalisation and effectiveness in government.

The British, since the initial failure in 1803, succeeded in conquering the Kandyan Kingdom in 1815, after which the whole island was reorganised into territorial, administrative and Judicial divisions merging earlier divisions and the five cardinal Provinces were established through the Proclamation of 30thSeptember 1833.It is well apparent from the proclamation that the new territorial divisions of the five cardinal provinces come about by the merger of already existing political divisions.

In constituting the five provinces, the breakdown of the Kandyan Kingdom came up along the lines of principalities that existed earlier known as Kandyan Provinces whose union was the Kandyan Kingdom.

When the proclamation regarding the establishment of the five provinces came up in 1833, the British have gained sufficient knowledge of the rights and claims of the Kandyan Kingdom as well as other political divisions that existed through the length and breadth of the country. The provinces did not come into existence by arbitrary drawing any line or territory. Though administrative considerations were an important factor, the provinces came about by effecting mergers of existing divisions of principalities and these were not arbitrary demarcation of areas made from the consideration of physical conveniences of the British officers as it is often claimed.

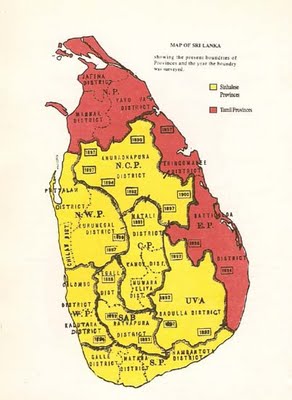

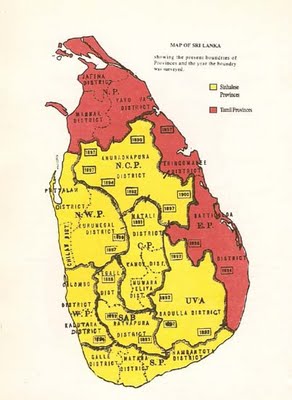

From Five to Nine

To put an end to the claims and confusion caused by the Tamil Sinhala divide that had now set in after the Kandyan conspiracy and with a view of further rationalising the boundaries of the division of five provinces so as to improve the effectiveness of the administration of the island , the British embarked on a laborious survey and investigation which took considerable energy of the British administration before arriving at the present boundaries of the nine provinces. The first change to the boundaries came about in 1837, and the final change in 1910 giving rise to the nine provinces from the original five. The extensive stretch of boundaries were surveyed and claims gone through in detail as regards the historical boundaries. The period between 1880 and 1910 saw the survey of every piece of boundary of the 9 provinces.

The cardinal five provinces were Western, Central, Northern, Southern and Eastern.

The Western province as constituted in 1833 comprised the Maritime portion of what is now known as North Western Province, the Districts of Ratnapura and Kegalle as well as what is now the Western Province. The Central Province included its present area and a major part of the present province of Uva.

The Northern Province included Nuwarakalaviya, now part of the North Central Province and the areas included within the present Northern Province.

The Southern Province included its present area, the Alupotha District of Badulla comprising Wellassa and Kandukara.

The Eastern Province included Thambankaduwa of the present North Central Province and Bintenne of the Badulla District and all land which presently consist the Eastern Province. In 1837, Bintenne which was part of the Eastern province was ceded to the Badulla District in the Central Province.

In 1845, the 6th province, the North Western, with the capital at Puttalam was constituted by annexations from the Western and Central Provinces.

In 1873, a 7th province was created in the name of North Central Province by bringing together Nuwarakalaviya of the Northern Province and Thambankaduwa of the Eastern Province and Demala Hatpattu of the North Western Province. In 1875, Demala Hatpattu was reattached to the North Western Province.

In 1886, the 8th Province Uva was formed by the detaching of the District of Badulla from the Central Province.

In 1889, the Districts of Kegalle and Ratnapura were severed from the Western Province and the Province of Sabragamuwa was constituted.

In 1870, the capital of the Eastern Province was transferred from Trincomalee to Batticaloa. The Vavuniya District was constituted in 1881 as a separate assistant agency and subsequently absorbed as such in 1900 and remained part of Mullaitivu District.

This evolution was made necessary not only from the standpoint of administrative convenience and effectiveness, but there were serious political compulsions in creating nine provinces. This was effected by merging and demerging traditional divisions where the natural alliance stood.

Though substantial areas which considered Tamil arrears were given away as Sinhalese provinces to meet the Sinhalese claims, to a very great extent, wherever these boundaries were distinguishable, the boundaries of the provinces went along the boundaries of the earlier principalities.

It is noteworthy that there were serious differences within the Sinhala provinces with regard to historical and traditional claims. The Provincial boundaries came about after consideration of various representations made regarding the historical boundaries.

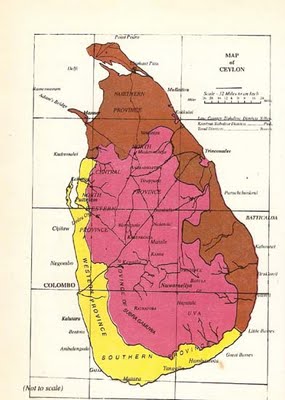

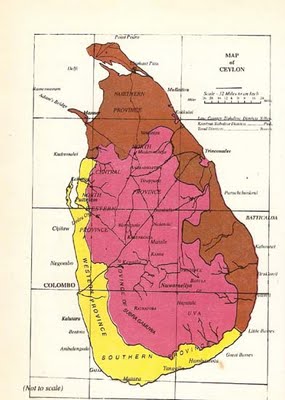

Map 1 The boundaries of the initial cardinal five Provinces. Land Maps and Surveys, R.L. Brohier .

Map 2 The boundaries of the nine provinces and the year when the survey of the boundary was completed. Land Maps and Surveys, R.L. Brohier .

The extent to which the British went in delimiting the boundaries when disputes arose is seen in the Bell’s memorandum on the dispute over Thammankaduwa -

Boundary between Tamankaduwa and the Eastern Province.

The "bone of contention" is the Egoda Pattuwa, or the Eastern- most division of Tamankaduwa on the further side (Egoda) of the Mahaveliganga. The question has been argued;

(i) historically, (ii) ethnologically, (iii) on administrative grounds (Fiscal, judicial and Registration), (iv) from the point of the desire and convenience of the inhabitants; and (v) as regards "natural boundary."

Serious differences arose regarding the claims over Adams Peak between Sabragamuwa and the Central Province. After protracted deliberations, the territory was left with Sabragamuwa and the boundary was accordingly proclaimed in 1915.

When going through these records, one understands the difficulties and virtual impossibility of merging the Sinhalese provinces, such is the nature of claims and antagonism that existed on either sides of the boundaries.

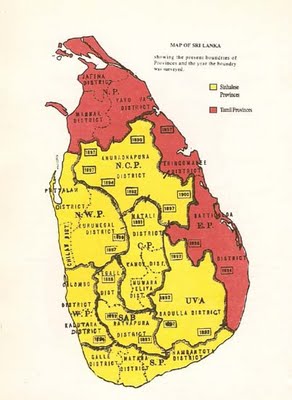

The Territory and Boundaries of the North East Tamil Provinces

However, the British, after conceding all claims of the Sinhalese from the earlier Northern and Eastern Provinces determined the boundary the two provinces as Tamil Provinces after conceding all Sinhalese claims. The Sinhalese claims and the British accommodation were very much conditioned by the perception all Kandyan territories were Sinhalese which it was not, as well as there was a Sinhala Buddhist Aryan civilisation in Sri Lanka which was a product of realm of imagination but purported to be real. This imagination was the foundation of establishment of North Central province. Much of the territories that were ceded from the cardinal North East as well as the creation of North Western Provinces included substantial territories that were well recognised Tamil and Veddha territories that have stood there for many centuries.

The name Tamil Province being used to indicate the two provinces of the North and East are apparent from the paragraph found in the Ceylon Manuel :-

With the other Tamil Province (Northern Province), the Eastern Province shares the honour of being the richest timber producing portion of the Island.- Ceylon Manual 1910: Page 313.

The recognition that the territory of these two provinces were Tamil is further evident from the paragraph of the Ceylon Manuel :

The Sinhalese & the Tamil districts - Ceylon is also divided into the Sinhalese district and the Tamil district. The former comprises the Western, Southern, Central, North-Western and North Central Provinces, with Uva and Sabragamuwa and the latter the Northern and Eastern Provinces. In the former the Sinhalese race and language predominate, and in the latter the Tamil. - Ceylon Manual - 1908 - Page 34.

The initial territorial boundaries of the Northern and Eastern provinces were determined by considering Jaffna and Trincomalee as their administrative capitals, taking into consideration the influence that these two centres of economic and political activity had over the respective areas.

The extent to which the British went in delimiting the boundaries when disputes arose is seen in the Bell’s memorandum on the dispute over Thammankaduwa -

Boundary between Tamankaduwa and the Eastern Province.

The "bone of contention" is the Egoda Pattuwa, or the Eastern- most division of Tamankaduwa on the further side (Egoda) of the Mahaveliganga. The question has been argued;

(i) historically, (ii) ethnologically, (iii) on administrative grounds (Fiscal, judicial and Registration), (iv) from the point of the desire and convenience of the inhabitants; and (v) as regards "natural boundary."

Serious differences arose regarding the claims over Adams Peak between Sabragamuwa and the Central Province. After protracted deliberations, the territory was left with Sabragamuwa and the boundary was accordingly proclaimed in 1915.

When going through these records, one understands the difficulties and virtual impossibility of merging the Sinhalese provinces, such is the nature of claims and antagonism that existed on either sides of the boundaries.

The Territory and Boundaries of the North East Tamil Provinces

However, the British, after conceding all claims of the Sinhalese from the earlier Northern and Eastern Provinces determined the boundary the two provinces as Tamil Provinces after conceding all Sinhalese claims. The Sinhalese claims and the British accommodation were very much conditioned by the perception all Kandyan territories were Sinhalese which it was not, as well as there was a Sinhala Buddhist Aryan civilisation in Sri Lanka which was a product of realm of imagination but purported to be real. This imagination was the foundation of establishment of North Central province. Much of the territories that were ceded from the cardinal North East as well as the creation of North Western Provinces included substantial territories that were well recognised Tamil and Veddha territories that have stood there for many centuries.

The name Tamil Province being used to indicate the two provinces of the North and East are apparent from the paragraph found in the Ceylon Manuel :-

With the other Tamil Province (Northern Province), the Eastern Province shares the honour of being the richest timber producing portion of the Island.- Ceylon Manual 1910: Page 313.

The recognition that the territory of these two provinces were Tamil is further evident from the paragraph of the Ceylon Manuel :

The Sinhalese & the Tamil districts - Ceylon is also divided into the Sinhalese district and the Tamil district. The former comprises the Western, Southern, Central, North-Western and North Central Provinces, with Uva and Sabragamuwa and the latter the Northern and Eastern Provinces. In the former the Sinhalese race and language predominate, and in the latter the Tamil. - Ceylon Manual - 1908 - Page 34.

The initial territorial boundaries of the Northern and Eastern provinces were determined by considering Jaffna and Trincomalee as their administrative capitals, taking into consideration the influence that these two centres of economic and political activity had over the respective areas.

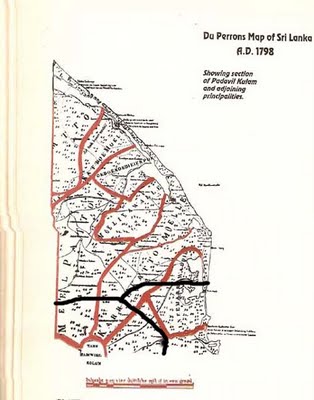

Map 3 Territory ceded to the Sinhalese between 1833 up to 1910.

Trincomalee was part of the Kingdom of Jaffna and at times an independent principality. Its importance as a centre of religious and political activity emanates from the existence of the natural harbour as well as the great religious centre of Koneswaram. The villages in the Trincomalee District are linked to the temple of Koneswaram through their servitude.

Writing on the history of the present boundaries of the Northern and Eastern Provinces; Mr. R.L. Brohier states:

(c) The Northern Province

This Province included according to the 1833 Proclamation, the maritime territory known as the "Provinces" of Jaffna, Mannar, the Vanni and the Island including Delft, together with the Kandyan territory known originally as the Disavany of Nuwarakalaviya.

The Province assumed its present limits by the exclusion of Nuwarakalaviya in 1873. The survey of a section of the boundary, from the point on the coast near Kokkilai, the South of Mullaithivu, was undertaken in 1890. The survey was to fulfil two objects: the first, to settle a disputed forest tract of the boundary, and the second, to obtain more information than was at the time available regarding the surrounding of the famous abandoned tank called Padavia, the bund of which had for long been accepted as a feature which fell on the Province boundary.

When the survey was eventually plotted, and the boundary was defined, Padavia tank was found actually to be several miles south of the proclaimed limits of the Province.

The Province boundary West of the North road was not taken up for survey until 1897. The section from Boragasveva which crossed the Mannar-Madavachiya road near the 44th mile post and contacts the Malvatu Oya, was surveyed by A.J. Whacker and the remaining section to the Moderagam Aru, by J.E.M. Ridout. The survey of the latter is supplemented by a specially well-documented report describing every feature along the boundary. The "historical boundary" between the Vanni and the Sinhalese territory lay in this belt of country. Consequently place, name and features acquired both a Sinhalese and a Tamil rendering. Ridout has entered both versions in his report, writing them in the respective vernacular scripts of which he seems to have had a good knowledge. This survey completed the definition of the boundary of the Northern Province.

(d) The Eastern Province

The Eastern Province consisted in 1833, of the maritime belt known as the "provinces" of Trincomalee and Batticaloa, together with the Kandyan territory called Tamankaduva and parts of the Bintanna extending South into what is today the Uva Province. The Uva Bintanna was transferred to the Central Province in 1837 and Tamankaduva was exercised and included in the North-Central Province in 1873. The province was consequently in its present form when Boundary Surveys were initiated in 1897 proved to be, in the words of the Surveyor General; "The most interesting of the Province Boundary Survey taken up." It followed the Yan Oya for a considerable distance.

Three years later another section starting from the point where the boundaries of three provinces meet at the Mahaveli Ganga, and terminating at the starting point of the section described earlier, was surveyed and defined. These two boundary surveys incidentally completed the definition of the boundaries of the North Central Province.

The survey and definition of the boundary abutting on the Disavany of Uva was done in 1894-96, and is discussed in the description of limits of the Province of Uva".

Though the British took the initiative to fuse the political divisions of the island into a unitary State, the British Colonial rulers attempted to placate the existence of the political divisions in various ways to reduce the tensions and apprehensions that arose in the process of assimilation. Competing claims for territory have existed not only between the two communities but also among the Sinhalese divisions from time immemorial.

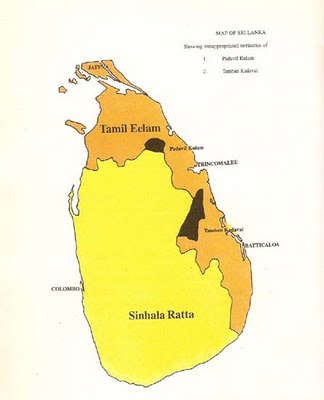

However the boundary line that divides the Northern and Eastern Provinces in the Mullaitheevu do not represent any political divisions. The strip which has become weakened as a result of misappropriation of territorial area of Padavil Kulam to the North Central Province, do not have any serious difference or antagonism on either side of territory. If the division would have been carried out along any historical boundary it would have been the boundary between two principalities under the Padavil Kulam which do not justify a division between them.

Mullaitivu was part of the Trincomalee district during the earlier division of Eastern province as well as during the Dutch period. Trincomalee was part of Jaffna during earlier times. These principalities ruled by Vanniahs on either side of the boundaries have maintained close political, economic and religious relationship.

Territorial Misappropriation in need of Reconsideration: Padavil Kulam Thamban Kadavai and Gal Oya.

The failure of the British Administrators to reinstate the boundaries over the Padavil Kulam has caused immense difficulties to the Tamils. The argument whether Padaviya, as it is now called, was part of Jaffna or not, came up during the Dutch period. In deciding the territory between Kandyan Kingdom and Dutch, the Kandyan claim to Padavil Kulam was rejected. The Dutch who were now versed in the schemes of the Kandyan Kingdom called in the Chiefs of Jaffna.

Trincomalee was part of the Kingdom of Jaffna and at times an independent principality. Its importance as a centre of religious and political activity emanates from the existence of the natural harbour as well as the great religious centre of Koneswaram. The villages in the Trincomalee District are linked to the temple of Koneswaram through their servitude.

Writing on the history of the present boundaries of the Northern and Eastern Provinces; Mr. R.L. Brohier states:

(c) The Northern Province

This Province included according to the 1833 Proclamation, the maritime territory known as the "Provinces" of Jaffna, Mannar, the Vanni and the Island including Delft, together with the Kandyan territory known originally as the Disavany of Nuwarakalaviya.

The Province assumed its present limits by the exclusion of Nuwarakalaviya in 1873. The survey of a section of the boundary, from the point on the coast near Kokkilai, the South of Mullaithivu, was undertaken in 1890. The survey was to fulfil two objects: the first, to settle a disputed forest tract of the boundary, and the second, to obtain more information than was at the time available regarding the surrounding of the famous abandoned tank called Padavia, the bund of which had for long been accepted as a feature which fell on the Province boundary.

When the survey was eventually plotted, and the boundary was defined, Padavia tank was found actually to be several miles south of the proclaimed limits of the Province.

The Province boundary West of the North road was not taken up for survey until 1897. The section from Boragasveva which crossed the Mannar-Madavachiya road near the 44th mile post and contacts the Malvatu Oya, was surveyed by A.J. Whacker and the remaining section to the Moderagam Aru, by J.E.M. Ridout. The survey of the latter is supplemented by a specially well-documented report describing every feature along the boundary. The "historical boundary" between the Vanni and the Sinhalese territory lay in this belt of country. Consequently place, name and features acquired both a Sinhalese and a Tamil rendering. Ridout has entered both versions in his report, writing them in the respective vernacular scripts of which he seems to have had a good knowledge. This survey completed the definition of the boundary of the Northern Province.

(d) The Eastern Province

The Eastern Province consisted in 1833, of the maritime belt known as the "provinces" of Trincomalee and Batticaloa, together with the Kandyan territory called Tamankaduva and parts of the Bintanna extending South into what is today the Uva Province. The Uva Bintanna was transferred to the Central Province in 1837 and Tamankaduva was exercised and included in the North-Central Province in 1873. The province was consequently in its present form when Boundary Surveys were initiated in 1897 proved to be, in the words of the Surveyor General; "The most interesting of the Province Boundary Survey taken up." It followed the Yan Oya for a considerable distance.

Three years later another section starting from the point where the boundaries of three provinces meet at the Mahaveli Ganga, and terminating at the starting point of the section described earlier, was surveyed and defined. These two boundary surveys incidentally completed the definition of the boundaries of the North Central Province.

The survey and definition of the boundary abutting on the Disavany of Uva was done in 1894-96, and is discussed in the description of limits of the Province of Uva".

Though the British took the initiative to fuse the political divisions of the island into a unitary State, the British Colonial rulers attempted to placate the existence of the political divisions in various ways to reduce the tensions and apprehensions that arose in the process of assimilation. Competing claims for territory have existed not only between the two communities but also among the Sinhalese divisions from time immemorial.

However the boundary line that divides the Northern and Eastern Provinces in the Mullaitheevu do not represent any political divisions. The strip which has become weakened as a result of misappropriation of territorial area of Padavil Kulam to the North Central Province, do not have any serious difference or antagonism on either side of territory. If the division would have been carried out along any historical boundary it would have been the boundary between two principalities under the Padavil Kulam which do not justify a division between them.

Mullaitivu was part of the Trincomalee district during the earlier division of Eastern province as well as during the Dutch period. Trincomalee was part of Jaffna during earlier times. These principalities ruled by Vanniahs on either side of the boundaries have maintained close political, economic and religious relationship.

Territorial Misappropriation in need of Reconsideration: Padavil Kulam Thamban Kadavai and Gal Oya.

The failure of the British Administrators to reinstate the boundaries over the Padavil Kulam has caused immense difficulties to the Tamils. The argument whether Padaviya, as it is now called, was part of Jaffna or not, came up during the Dutch period. In deciding the territory between Kandyan Kingdom and Dutch, the Kandyan claim to Padavil Kulam was rejected. The Dutch who were now versed in the schemes of the Kandyan Kingdom called in the Chiefs of Jaffna.

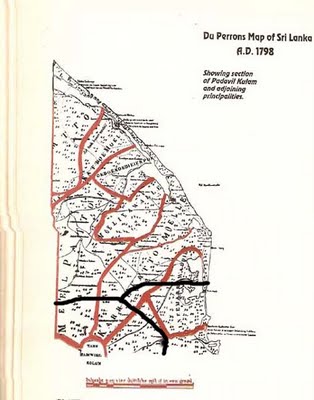

Map 4. The Du Perron's Map of Ceylon A.D. 1798 showing Padavil Kulam and the adjoining principalities. The current boundary ( black line) showing the extended Sinhalese territory that now cuts the Padavil Kulam area as well as the division between the North East drawn without any basis and disregarding the traditional boundaries of Tamil principalities. Land Maps and Surveys. R.L. Brohier.

The Padavil Kulam bund which was a historical land mark in the southern boundary of the territories of the Kingdom of Jaffna was left as part of the Northern territory. The territory beyond, between the boundary of the Principality of Anuradhapuram including the catchment area of the Padavil Kulam Tank, was a well recognised Veddha Territory that can be seen in all the maps showing divisions of principalities.

As revealed in Du Peron’s map the boundaries of the various principalities under the Padavil Kulam such as Melpattu, Karikattumoolai, Thennamaravadi initiated and radiated from the bund of the Pathavil Kualm Tank. However the present boundary of the Northern Province cuts these principalities in half, violating the traditional norms and historical boundaries.

One has to look to reasons other than the petty claims of the Sinhalese, for British failing to reinstate the traditional boundary even after it was known that it has been misappropriated.

On the western side, the historical boundaries between Vanni and Sinhalese territory in reality went along the boundaries of Demala Hatpattuwa which is now in the North Central Province. However, this too was ignored and the boundary was made to start from Moderagam Aru.

Considerable debate and representations took place regarding Thamban Kadavai (Thamankaduwa) East which is also known as Egodapattu and was inhabited by Tamils and Veddahs from ancient times. According to the Portuguese, Thamban Kadavai was peopled by Tamils who were converted to Christianity. The historical boundaries went along the Mahaweli river.

Bell’s memorandum on Thammankaduwa reveals the issues that were considered in deciding the boundary between Eastern and North Western Province. The British have also adopted the straight line boundary separating Thamban Kadavai from the East, a principle not known in Sri Lanka, revealing the boundary as not the historical boundary of any principality or political division based on traditional boundaries.

One can clearly see that the British went out of the way in annexing these two areas of Padavil Kulam and Thamban Kadavai to the Sinhalese territories. Apart from the fact that they have attempted to please the majority Sinhalese in improperly annexing these areas from the North East Province, there is no doubt that the British have narrowed the linkage that existed between the districts of Trincomalee with Jaffna and Batticaloa as they had their own designs on Trincomalee.

Added to this is the refusal of the British to develop linkages through these land strips such as roads etc. that kept the Trincomalee district away from the Tamils of Jaffna and Batticaloa. It is also seen in shifting the capital of the Eastern Province from Trincomalee to Batticaloa in 1870.

There is also another reason why the British have gone out of the way in demarcating traditional Tamil areas as Kandyan and Sinhalese areas. That was the need to indemnify the appropriation of Kandyan Royal Lands after the expulsion of the Kandyan Royalty to Vellore in India and the banishment of Tamils from the Kandyan Kingdom, which was to be used for their plantation economy.

Map 5. The misappropriated areas of Padavil Kulam, Thamban Kadavai and Gal Oya.

Appropriation of such large tracts of land encompassing the North Central and North Western Provinces over which the Kandyan Kingdom had a feeble control for a short period also enabled the British to demarcate the Nuwra Eliya district as a area for the plantation Tamils on the hill country. This area was thick impregnable jungle during the time of Kandyan Kings which the British opened up for plantation with the help of up country Tamils. .

The Importance of names of villages

It is important to note that when the boundaries become untraceable, the principle that was adopted to mark the boundaries of the Tamil province was by identifying the Tamil names of villages. The boundaries were drawn leaving, on one side the Tamil villages and on the other side, the Sinhalese sounding village names which in most cases was Veddha villages. The middle path along which the boundary went was found by linking villages which had names in both languages where people were in some form of cultural, linguistic flux, subject to social, political and economic influences from both sides. Most of what was given away as Sinhalese areas was in fact Veddha territories.

The adoption of this principle is relevant even today when serious disputes have arisen with regard to claims of territories and an attempt is made to carve out more territory using the Sinhalese who have been recently settled.

The prevalence of this tradition of identifying whether a Village is Tamil or Sinhalese from the name also explains why the Sinhalese are so desperate to create Sinhalese sounding village names in the North East. Turning a Tamil village into a Sinhalese village can be carried out by two ways. Either the name came be twisted by the tail to make it sound Sinhalese name or are translated into Sinhalese.

The traditional right of the Tamil people over the North East emanates from the traditional right of the Tamil villages. These rights include their rights over seas, forests and water.

The customary rights of these villages have been in practice as long as these villages have been in existence and were recognised by the sovereign process.

The Veddha Territory of the East

Substantial territory of the Eastern Province known as Bintenna was ceded to the Sinhalese when the North Western Province and Uva Province were created. A part of the Veddha principalities of Wewagam Pattu and Bintenne Pattu were left with the Eastern Province. This was mainly due to the fact that the Veddahs who lived in these areas maintained close economic, cultural and religious relationships with the Tamil principalities and paid tributes to the chieftains of these principalities.

Today as a result of the Sinhalese schemes, the claims of the Veddhas of Bintenne whose territorial right over Bintenne was recognised during the Kandyan period, have completely disappeared. Only Sinhalese fugitives were banished to these areas during the Kandyan times.

Much of the area that has been developed under the Mahavali Project was the Veddhas principality of Bintenne. Considerable area of the Amparai district was Veddha territory which had close links to the Tamil principalities of the East.

The Veddhas of the Eastern Province have suffered considerably as a result of Sinhalese settlements and schemes.

The Veddas live off the Jungles like the fisherman live off the seas. The natural endowment of the jungle provide them with livelihood. The marauding Portuguese could hardly recognise them. The interior jungles kept them away from the Dutch and the British. But before the arrival of these interlopers, the Veddhas led a life as a recognised community. The Veddhas are not used to a settled cast based village life, as their migratory habit is very essential for their livelihood, without which their survival is not possible. The villages of the surrounding areas depend on the Veddhas for the cultivation of the jungle produce like hony and venison. Before the arrival of the Europeans there existed a very useful and complementary economic relationship between the Tamil principalities and the Veddha principalities.

Today the chauvinist schemes have completely swallowed up the Veddhas and their way of life and most of the Veddas have taken refuge in the Tamil villages of the East and have become Tamils and Tamil villages. Another section has also been assimilated as Sinhalese.

Commenting on the extent of the Vedda territory C.G.Seligmann who did extensive research about the Veddas during the early part of this century says;-

The Veddah country at the present day is limited to a roughly triangular tract lying between the eastern slopes of the central mountain massive and the sea. This area of about 2400 square miles is bounded on the west by the Mahaweli Ganga, from the point where, abandoning its eastern course through the mountains of the Central Province, the river sweeps northwards to the sea. A line from this great bend passing eastwards through Bibile village (on the Badulla - Batticaloa road) to the coast will define the southern limits of the Veddah country with sufficient accuracy, while its eastern limit is the coast.

So defined it includes the greater part of the Eastern Province, about a fifth of Uva and a small portion of that part of the North Central Province known as Tamankaduwa, and is traversed by a single high road capable of taking wheeled traffic. This runs from Badulla , the Capital of Uva, lying at the foot of the central mountain mass of the island, to the coast a few miles to the north of Batticaloa, the capital of the Eastern Province.

Here flows the Mahaweli Ganga, soon to be hidden in the great sea of forest-clad lowland stretching away to the north, from which rise Kogkalle and other hills, the traditional homes the Veddas, like rocky islands in the distance. To the east tower the Uva mountains, stretching onwards in a diminishingseries towards the uplands of Nilgala. In Bintenne, including in this term parts of both Uva and the Eastern Province, the jungle consists of a forest of great trees without much undergrowth, occasionally interrupted by open spaces, covered with coarse grass, which, however, does not grow much higher than the knee. These open patches are more numerous in the Eastern province than they are in Uva Bintenne (which is traversed by many small streams) and it is generally supposed that there are sites of ancient cultivation; there are comparatively few streams in this country though swamps and small water holes containing stagnant water are common.

Northward in Tamankaduwa (a division of the North Central Province) the great trees give place to poorer growth and scrubby jungle is found. On the east of the Badulla-Batticaloa road lie the Nilgala hills, the best of the Veddas domain and the most pleasing country in Ceylon. Here, broad valleys lie between jungle-clad ranges of much weathered gneiss, among whose rocky crags and rounded domes, bambara, the rock bee (Apis indica), builds its combs.

The coastal zone north of Batticaloa inhabited by the coast Veddas is flat and sandy, and the vegetation though dense is often less tall and less abundant than in other parts of the country.

Formally the Veddas country is known to have embraced the whole of the Uva, and much of the Central and North Central Provinces, while there is no reason to suppose that their territory did not extend beyond these limits. Indeed there is no reasonable doubt that the Veddas are identical with the "Yakkas" of the Mahavamsa and other native chronicles.

-The Veddas. C.G.Sligmann & Brenda Z.Seligmann, page 1-4

The Veddhas have become part of the Tamil villages and have risen to important positions among the Tamil community. Lately the Veddha youth have joined the ranks of Tamil militant groups, were members of the North East Provincial council and have risen to become ministers in the government. These youths were often cause for the raid into Sinhalese settlements in the East.

The Sinhalese Sounding Villages of the East

Historically, there are five types of villages that have Sinhalese sounding names in the East.

(1) The Veddah Villages that are part of the erstwhile Batticaloa district mainly from the Bintenne Pattu and Wewagam Pattu;

(2) The Sinhalese refugees villages before the Kandyan period;

(3) The Sinhalese village settlements that came along the pathway that was allowed to the Kandyan Kingdom by the Tamil principalities by granting the right of passage to the East coast;

(4) The villages of the Kandyan Sinhalese seeking refuge from the British take-over and repression against the Kandyan rebellions;

(5) The villages that came about as a result of State aided colonisation in recent times.

These are the so called Sinhala settlements in the Eastern Province which have become the basis for carving out new territory by the Sinhalese today. The Sinhalese settlements were known by the name Kudies, a peculiar clan tradion of Batticaloa and were an integral part of the socio political structures of the Tamil principalities.

The Political Status of Muslim Villages in the East.

From very early times the dominant Mukkuvas of Batticaloa and the Muslims seems to have a peculiar relationship between them. The early settlements of the Muslims appear through the Muslims marrying Tamil women in the East. Due to the persecution of the Muslims by the Portuguese and Dutch in cinnamon producing areas of the South, and decline of Muslims influence in trade and commerce, a considerable number of Muslim villages appeared in the East. Added to this was the Kandyan habit of not allowing the Muslim to take refuge in the Kandyan territory but allowing them to go through the Kandyan Kingdom and settle in villages of the East through the back door some of which had become depopulated as a result of Portuguese and Dutch repressive measures.

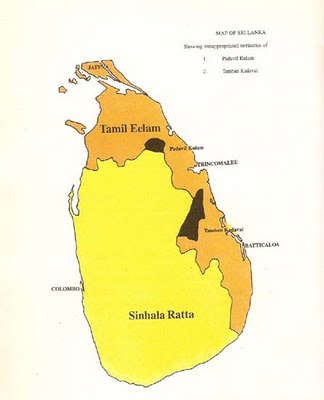

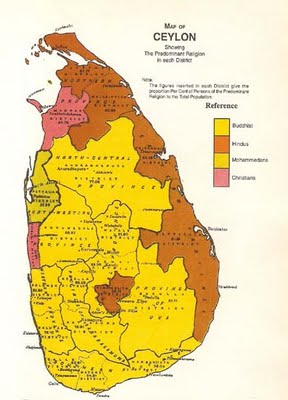

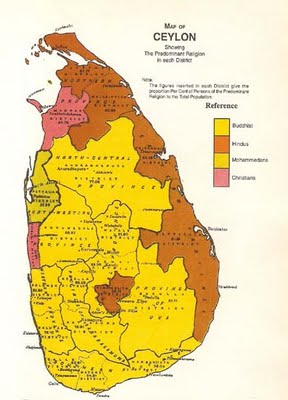

Map 6. Ethno territorial divisions that appeared in the Ceylon Manuel 1905 and Census of 1911.

There is no history of any Muslim principality or a territory over which the Muslim held political authority in the East or the North. In subsequent days during the Dutch period smaller divisions such as Sammanthurai Pattu were recognised as Muslim divisions.

When the territorial demarcation of various communities appeared along with the division of principal nationalities during the early part of this century the maps do not show any Muslim division in the East. The fact that these maps appear in many official documents shows that this demarcation was not an accidental event. A territory is demarcated and shown as Muslim territory only in the Puttalam district of North Western Province even though the Muslim population is shown to be only thirty percent during the beginning of the last centaury. This has come down to 12 percent due to Sinhalese schemes in recent times.

This territorial demarcation of the Muslims in the North Western Province has come about as a result of the existence of historical rights of the Muslim community for the territory and it is not affected whether the Muslims are a minority there or few in number. This territorial division of Puttalam as a Muslims territory has come into existence, like the Mukkuva settlement of Batticaloa, during the period of Kingdom of Jaffna as Portuguese have fought wars with he Muslim chieftains of the area. What remains as territorial demarcation of Muslims which was once ceded a Muslim territory by the Tamils should remain as such and there is no need to reclaim it as Tamil area.

Kudy names of Muslims

The British civil Servant Mr Hugh Neville Esq. who took great pains to record the socio political conditions of the East between 1860 and 1880 records nearly 21 Muslim Kudy (clan) in the Batticaloa District.

The Muslims taking the name Kudy or Clan is indicative of them accepting the political norms that were prevalent in the Tamil principalities of the East where they have come to take refuge and settle down. Added to this is the cultural and literary interaction that has existed as a result of sharing a common heritage of language and culture.

The Muslims and Tamils have lived side by side and shared the economic life of the East. Only after the advent of divisive democratic politics and rise of fundamentalism in Muslim political life there arose discord among the Tamil and Muslim communities in the East. The intricate relationship the Eastern Muslims have developed with the Tamils starting from inter marriage has led to a peculiar love hate relationship between the two communities and their demographic spread in the east is such making any demarcation between them either territorial or otherwise is impossible.

Though Muslim politicians in Colombo who have little understanding of the situation in the East or Jaffna Tamils who have difficulty in comprehending this intricate relationship have done little to help in reducing the tensions that prevail between the two communities. However, the problem of congestion that is found in the East can only be solved through expanding the space and opportunities though the permanent merger of the North East.

From very early times the dominant Mukkuvas of Batticaloa and the Muslims seems to have a peculiar relationship between them. The early settlements of the Muslims appear through the Muslims marrying Tamil women in the East. Due to the persecution of the Muslims by the Portuguese and Dutch in cinnamon producing areas of the South, and decline of Muslims influence in trade and commerce, a considerable number of Muslim villages appeared in the East. Added to this was the Kandyan habit of not allowing the Muslim to take refuge in the Kandyan territory but allowing them to go through the Kandyan Kingdom and settle in villages of the East through the back door which had become depopulated as a result of Portuguese and Dutch repressive measures.

Muslims and Tamils of the East are divided only by religion. Ethnologically. linguistically, economically , territorially and culturally they are so integrated, a separation is virtually impossible.

The Territorial Divisions of Principal Nationalities

The further recognition of the merged Northeast as Tamil Homeland appears in the Ceylon Manual as division of the Principal Nationalities showing the three territorial divisions of the Principal Nationalities namely those of Kandyan Sinhalese, Low Country Sinhalese and Tamils.

The Padavil Kulam bund which was a historical land mark in the southern boundary of the territories of the Kingdom of Jaffna was left as part of the Northern territory. The territory beyond, between the boundary of the Principality of Anuradhapuram including the catchment area of the Padavil Kulam Tank, was a well recognised Veddha Territory that can be seen in all the maps showing divisions of principalities.

As revealed in Du Peron’s map the boundaries of the various principalities under the Padavil Kulam such as Melpattu, Karikattumoolai, Thennamaravadi initiated and radiated from the bund of the Pathavil Kualm Tank. However the present boundary of the Northern Province cuts these principalities in half, violating the traditional norms and historical boundaries.

One has to look to reasons other than the petty claims of the Sinhalese, for British failing to reinstate the traditional boundary even after it was known that it has been misappropriated.

On the western side, the historical boundaries between Vanni and Sinhalese territory in reality went along the boundaries of Demala Hatpattuwa which is now in the North Central Province. However, this too was ignored and the boundary was made to start from Moderagam Aru.

Considerable debate and representations took place regarding Thamban Kadavai (Thamankaduwa) East which is also known as Egodapattu and was inhabited by Tamils and Veddahs from ancient times. According to the Portuguese, Thamban Kadavai was peopled by Tamils who were converted to Christianity. The historical boundaries went along the Mahaweli river.

Bell’s memorandum on Thammankaduwa reveals the issues that were considered in deciding the boundary between Eastern and North Western Province. The British have also adopted the straight line boundary separating Thamban Kadavai from the East, a principle not known in Sri Lanka, revealing the boundary as not the historical boundary of any principality or political division based on traditional boundaries.

One can clearly see that the British went out of the way in annexing these two areas of Padavil Kulam and Thamban Kadavai to the Sinhalese territories. Apart from the fact that they have attempted to please the majority Sinhalese in improperly annexing these areas from the North East Province, there is no doubt that the British have narrowed the linkage that existed between the districts of Trincomalee with Jaffna and Batticaloa as they had their own designs on Trincomalee.

Added to this is the refusal of the British to develop linkages through these land strips such as roads etc. that kept the Trincomalee district away from the Tamils of Jaffna and Batticaloa. It is also seen in shifting the capital of the Eastern Province from Trincomalee to Batticaloa in 1870.

There is also another reason why the British have gone out of the way in demarcating traditional Tamil areas as Kandyan and Sinhalese areas. That was the need to indemnify the appropriation of Kandyan Royal Lands after the expulsion of the Kandyan Royalty to Vellore in India and the banishment of Tamils from the Kandyan Kingdom, which was to be used for their plantation economy.

Map 5. The misappropriated areas of Padavil Kulam, Thamban Kadavai and Gal Oya.

Appropriation of such large tracts of land encompassing the North Central and North Western Provinces over which the Kandyan Kingdom had a feeble control for a short period also enabled the British to demarcate the Nuwra Eliya district as a area for the plantation Tamils on the hill country. This area was thick impregnable jungle during the time of Kandyan Kings which the British opened up for plantation with the help of up country Tamils. .

The Importance of names of villages

It is important to note that when the boundaries become untraceable, the principle that was adopted to mark the boundaries of the Tamil province was by identifying the Tamil names of villages. The boundaries were drawn leaving, on one side the Tamil villages and on the other side, the Sinhalese sounding village names which in most cases was Veddha villages. The middle path along which the boundary went was found by linking villages which had names in both languages where people were in some form of cultural, linguistic flux, subject to social, political and economic influences from both sides. Most of what was given away as Sinhalese areas was in fact Veddha territories.

The adoption of this principle is relevant even today when serious disputes have arisen with regard to claims of territories and an attempt is made to carve out more territory using the Sinhalese who have been recently settled.

The prevalence of this tradition of identifying whether a Village is Tamil or Sinhalese from the name also explains why the Sinhalese are so desperate to create Sinhalese sounding village names in the North East. Turning a Tamil village into a Sinhalese village can be carried out by two ways. Either the name came be twisted by the tail to make it sound Sinhalese name or are translated into Sinhalese.

The traditional right of the Tamil people over the North East emanates from the traditional right of the Tamil villages. These rights include their rights over seas, forests and water.

The customary rights of these villages have been in practice as long as these villages have been in existence and were recognised by the sovereign process.

The Veddha Territory of the East

Substantial territory of the Eastern Province known as Bintenna was ceded to the Sinhalese when the North Western Province and Uva Province were created. A part of the Veddha principalities of Wewagam Pattu and Bintenne Pattu were left with the Eastern Province. This was mainly due to the fact that the Veddahs who lived in these areas maintained close economic, cultural and religious relationships with the Tamil principalities and paid tributes to the chieftains of these principalities.

Today as a result of the Sinhalese schemes, the claims of the Veddhas of Bintenne whose territorial right over Bintenne was recognised during the Kandyan period, have completely disappeared. Only Sinhalese fugitives were banished to these areas during the Kandyan times.

Much of the area that has been developed under the Mahavali Project was the Veddhas principality of Bintenne. Considerable area of the Amparai district was Veddha territory which had close links to the Tamil principalities of the East.

The Veddhas of the Eastern Province have suffered considerably as a result of Sinhalese settlements and schemes.

The Veddas live off the Jungles like the fisherman live off the seas. The natural endowment of the jungle provide them with livelihood. The marauding Portuguese could hardly recognise them. The interior jungles kept them away from the Dutch and the British. But before the arrival of these interlopers, the Veddhas led a life as a recognised community. The Veddhas are not used to a settled cast based village life, as their migratory habit is very essential for their livelihood, without which their survival is not possible. The villages of the surrounding areas depend on the Veddhas for the cultivation of the jungle produce like hony and venison. Before the arrival of the Europeans there existed a very useful and complementary economic relationship between the Tamil principalities and the Veddha principalities.

Today the chauvinist schemes have completely swallowed up the Veddhas and their way of life and most of the Veddas have taken refuge in the Tamil villages of the East and have become Tamils and Tamil villages. Another section has also been assimilated as Sinhalese.

Commenting on the extent of the Vedda territory C.G.Seligmann who did extensive research about the Veddas during the early part of this century says;-

The Veddah country at the present day is limited to a roughly triangular tract lying between the eastern slopes of the central mountain massive and the sea. This area of about 2400 square miles is bounded on the west by the Mahaweli Ganga, from the point where, abandoning its eastern course through the mountains of the Central Province, the river sweeps northwards to the sea. A line from this great bend passing eastwards through Bibile village (on the Badulla - Batticaloa road) to the coast will define the southern limits of the Veddah country with sufficient accuracy, while its eastern limit is the coast.

So defined it includes the greater part of the Eastern Province, about a fifth of Uva and a small portion of that part of the North Central Province known as Tamankaduwa, and is traversed by a single high road capable of taking wheeled traffic. This runs from Badulla , the Capital of Uva, lying at the foot of the central mountain mass of the island, to the coast a few miles to the north of Batticaloa, the capital of the Eastern Province.

Here flows the Mahaweli Ganga, soon to be hidden in the great sea of forest-clad lowland stretching away to the north, from which rise Kogkalle and other hills, the traditional homes the Veddas, like rocky islands in the distance. To the east tower the Uva mountains, stretching onwards in a diminishingseries towards the uplands of Nilgala. In Bintenne, including in this term parts of both Uva and the Eastern Province, the jungle consists of a forest of great trees without much undergrowth, occasionally interrupted by open spaces, covered with coarse grass, which, however, does not grow much higher than the knee. These open patches are more numerous in the Eastern province than they are in Uva Bintenne (which is traversed by many small streams) and it is generally supposed that there are sites of ancient cultivation; there are comparatively few streams in this country though swamps and small water holes containing stagnant water are common.

Northward in Tamankaduwa (a division of the North Central Province) the great trees give place to poorer growth and scrubby jungle is found. On the east of the Badulla-Batticaloa road lie the Nilgala hills, the best of the Veddas domain and the most pleasing country in Ceylon. Here, broad valleys lie between jungle-clad ranges of much weathered gneiss, among whose rocky crags and rounded domes, bambara, the rock bee (Apis indica), builds its combs.

The coastal zone north of Batticaloa inhabited by the coast Veddas is flat and sandy, and the vegetation though dense is often less tall and less abundant than in other parts of the country.

Formally the Veddas country is known to have embraced the whole of the Uva, and much of the Central and North Central Provinces, while there is no reason to suppose that their territory did not extend beyond these limits. Indeed there is no reasonable doubt that the Veddas are identical with the "Yakkas" of the Mahavamsa and other native chronicles.

-The Veddas. C.G.Sligmann & Brenda Z.Seligmann, page 1-4

The Veddhas have become part of the Tamil villages and have risen to important positions among the Tamil community. Lately the Veddha youth have joined the ranks of Tamil militant groups, were members of the North East Provincial council and have risen to become ministers in the government. These youths were often cause for the raid into Sinhalese settlements in the East.

The Sinhalese Sounding Villages of the East

Historically, there are five types of villages that have Sinhalese sounding names in the East.

(1) The Veddah Villages that are part of the erstwhile Batticaloa district mainly from the Bintenne Pattu and Wewagam Pattu;

(2) The Sinhalese refugees villages before the Kandyan period;

(3) The Sinhalese village settlements that came along the pathway that was allowed to the Kandyan Kingdom by the Tamil principalities by granting the right of passage to the East coast;

(4) The villages of the Kandyan Sinhalese seeking refuge from the British take-over and repression against the Kandyan rebellions;

(5) The villages that came about as a result of State aided colonisation in recent times.

These are the so called Sinhala settlements in the Eastern Province which have become the basis for carving out new territory by the Sinhalese today. The Sinhalese settlements were known by the name Kudies, a peculiar clan tradion of Batticaloa and were an integral part of the socio political structures of the Tamil principalities.

The Political Status of Muslim Villages in the East.

From very early times the dominant Mukkuvas of Batticaloa and the Muslims seems to have a peculiar relationship between them. The early settlements of the Muslims appear through the Muslims marrying Tamil women in the East. Due to the persecution of the Muslims by the Portuguese and Dutch in cinnamon producing areas of the South, and decline of Muslims influence in trade and commerce, a considerable number of Muslim villages appeared in the East. Added to this was the Kandyan habit of not allowing the Muslim to take refuge in the Kandyan territory but allowing them to go through the Kandyan Kingdom and settle in villages of the East through the back door some of which had become depopulated as a result of Portuguese and Dutch repressive measures.

Map 6. Ethno territorial divisions that appeared in the Ceylon Manuel 1905 and Census of 1911.

There is no history of any Muslim principality or a territory over which the Muslim held political authority in the East or the North. In subsequent days during the Dutch period smaller divisions such as Sammanthurai Pattu were recognised as Muslim divisions.

When the territorial demarcation of various communities appeared along with the division of principal nationalities during the early part of this century the maps do not show any Muslim division in the East. The fact that these maps appear in many official documents shows that this demarcation was not an accidental event. A territory is demarcated and shown as Muslim territory only in the Puttalam district of North Western Province even though the Muslim population is shown to be only thirty percent during the beginning of the last centaury. This has come down to 12 percent due to Sinhalese schemes in recent times.

This territorial demarcation of the Muslims in the North Western Province has come about as a result of the existence of historical rights of the Muslim community for the territory and it is not affected whether the Muslims are a minority there or few in number. This territorial division of Puttalam as a Muslims territory has come into existence, like the Mukkuva settlement of Batticaloa, during the period of Kingdom of Jaffna as Portuguese have fought wars with he Muslim chieftains of the area. What remains as territorial demarcation of Muslims which was once ceded a Muslim territory by the Tamils should remain as such and there is no need to reclaim it as Tamil area.

Kudy names of Muslims

The British civil Servant Mr Hugh Neville Esq. who took great pains to record the socio political conditions of the East between 1860 and 1880 records nearly 21 Muslim Kudy (clan) in the Batticaloa District.

The Muslims taking the name Kudy or Clan is indicative of them accepting the political norms that were prevalent in the Tamil principalities of the East where they have come to take refuge and settle down. Added to this is the cultural and literary interaction that has existed as a result of sharing a common heritage of language and culture.

The Muslims and Tamils have lived side by side and shared the economic life of the East. Only after the advent of divisive democratic politics and rise of fundamentalism in Muslim political life there arose discord among the Tamil and Muslim communities in the East. The intricate relationship the Eastern Muslims have developed with the Tamils starting from inter marriage has led to a peculiar love hate relationship between the two communities and their demographic spread in the east is such making any demarcation between them either territorial or otherwise is impossible.

Though Muslim politicians in Colombo who have little understanding of the situation in the East or Jaffna Tamils who have difficulty in comprehending this intricate relationship have done little to help in reducing the tensions that prevail between the two communities. However, the problem of congestion that is found in the East can only be solved through expanding the space and opportunities though the permanent merger of the North East.

From very early times the dominant Mukkuvas of Batticaloa and the Muslims seems to have a peculiar relationship between them. The early settlements of the Muslims appear through the Muslims marrying Tamil women in the East. Due to the persecution of the Muslims by the Portuguese and Dutch in cinnamon producing areas of the South, and decline of Muslims influence in trade and commerce, a considerable number of Muslim villages appeared in the East. Added to this was the Kandyan habit of not allowing the Muslim to take refuge in the Kandyan territory but allowing them to go through the Kandyan Kingdom and settle in villages of the East through the back door which had become depopulated as a result of Portuguese and Dutch repressive measures.

Muslims and Tamils of the East are divided only by religion. Ethnologically. linguistically, economically , territorially and culturally they are so integrated, a separation is virtually impossible.

The Territorial Divisions of Principal Nationalities

The further recognition of the merged Northeast as Tamil Homeland appears in the Ceylon Manual as division of the Principal Nationalities showing the three territorial divisions of the Principal Nationalities namely those of Kandyan Sinhalese, Low Country Sinhalese and Tamils.

Map 7. The Territorial Division of Principal Nationalities, Tamil. Kandyan and Low Country Sinhalese as it appeared in the official documents of Government of Ceylon during early part of last century.

The basic difference in the classification of a community as a nationality rather than a minority lies in the existence of a history of having lived on a defined territory and held power distinguished by its congruent authority structures apart from the common identity factors such as language, religion, culture and race. A minority community, though is distinguished by a common language, religion and culture, for its survival, it depends on another community as a dependent community. Minorities are not distinguished by a history of their territory and political authority structures and a history of self government.

In identifying the principal nationalities and minorities during the early days of the formation of the Ceylonese nation, which can be seen in the demarcation of territories of principal nationalities, and ethnological maps. all important historical and political considerations were taken into account.

The Durbars of Native Chiefs

Further recognition by the British that these two provinces of North and East constituted one political unit of Tamil Homeland, came in the Durbar held for the Provinces of North East together during the early period of this century.

The Governors address to the Legislature on the August 26 1908 had this vital reference indicating the political foundations of the Durbars.

There is one other point I should like you to discuss before you dissolve, as to the desirability and as to the advisability of carrying out an idea which has occurred to me - an idea which, I believe is not new in this Colony, although it has not been carried into effect for a large number of years. That is, to have before long a Durbar of Native Chiefs - of the principal ruling headmen of the country in order to discuss with them subjects of interest to ourselves and Government and also of interest to themselves, and to learn personally from them their ideas in a Durbar.

Time did not admit of the subject being discussed at the Conference, but after consultation by letter with the Government Agents I eventually decided hold three Durbars, one at Kandy for Kandyans, one at Colombo for Low-country Sinhalese, and later on one probably at Jaffna for Tamil headman. This course is, I think, preferable to holding one big durbar, which , though it would undoubtedly be more picturesque and imposing, would probably result in less practical discussion, while it would simultaneously denude all parts of the Island of important links in the chain of supervision for several days at a time.

The first two durbars have already been held, the first at Kandy in May and the second at Colombo in July. At both meetings the Government Agents of the Provinces concerned attended, in addition to representative chiefs from each Province. Among the subjects discussed at Kandy, where the experiment proved especially successful, were the illicit sale of arrack and toddy Sinhalese labour for estates, stray cattle on roads, and protection of fresh water fish. Of these, the first three were also discussed in Colombo. At the latter durbar I also sought to ascertain the views of the Mudaliyars as to whether there was any feasible plan for mitigating the perennial evils arising from the infinitesimal subdivision of undivided shares in land.The subject was freely discussed and various suggestions made, but I regret to say that the only result was to prove beyond doubt that the matter is not ripe for any action at present"

The merger of the provinces into territories of principal nationalities has come to signify the existence of uniformity of authority structures provided by the kingdoms of Jaffna, Kotte and Kandy. The most striking anomaly in the whole exercise is the bifurcation of the North Western Province into Kandyan and Low Country areas and the respective chiefs taking part in the Durbar of Kandyan Chiefs and the Durbar of the Low Country Chiefs. (See map 6).

The Kandyan claims to a part of the North Western Province which was not ceded to the Dutch was upheld and duly this territory was made part of the Kandyan territory and the Native Chiefs of these areas were allowed to take part in the Kandyan Durbar.

It is also evident from this event that if the Kandyans would have had any claim to any part of Eastern Province this too would have come up for deliberation and these areas too would have been brought under the Kandyan territory. However such a demand was non existent during this period or anytime after since the demarcation of the present Northern and Eastern provinces.

The Durbars were held between 1908 and 1912. The Durbars of North East were held In Colombo in 1908, Jaffna in 1910 and Batticaloa in 1912.

The Durbars of the territory of the Low Country Sinhalese were held in Colombo and the Durbars of the Kandyan Territory were held in Kandy.

The Council of Durbars seems to have come to an end with the departure of Governor McCallum (1907- 1913), who has exhibited unprecedented vision not found in any other British Governor in initiating and conducting the Durbars. The trend set by Governor McCallum was not pursued by the Tamil leadership which was more interested in promoting the idea of Ceylonese Nation and impressing the white man with their silver tongued oratory and losing sight of their own people and their homeland. The event was soon overshadowed by the chase of the wild goose in the search of a stable constitution which has not come to an end even after 100 years.

The realistic foundation laid by Governor McCullum came to be buried in the over growth of the cancerous chauvinist agenda to which the Sinhala race came to be hooked on by the scheming politicians and the duly recorded and printed Proceedings of the Durbars have disappeared even from the Archives of Sri Lanka.

Providing for political realities

The divisions and demarcation that came up during the British period that lasted for nearly 150 years of their rule are important and has to be adhered to if Sri Lanka is to be a peaceful nation. These are not arbitrary divisions as some claim. In spite of their short comings, a united Sri Lanka we know is an achievement of the British. Since the Proclamation of 1833 bringing to existence the united Sri Lanka, there has bee an relentless pursuit by the British authorities, spanning for over 120 years, to harmoniously integrate, Sri Lanka and to leave behind a peaceful united Sri Lanka.

Any united rule of the earlier period belongs to the Kingdom of Jaffna that lasted from the 13th century to the 16th century. The rule of Kingdom of Jaffna was based on highly autonomous principalities. To discard the contours of divisions and anchor Sri Lanka on the foundation of historical claims based on an illusionary Sinhala Buddhist state that never existed in history will eventually bring about collapse to the Sri Lankan state due to its unrealistic and unsustainable nature.

The contradiction between a plural unitary state and a Sinhala only Buddhist state where minorities will be subject to discrimination has become the major contradiction of the political history of independent Sri Lanka. These two verities of state are not one and the same and no one will succeed in selling the two ideas as combatable. Whereas as freedom of Sri Lanka is the freedom of all her citizens, the freedom of the Sinhalese is the freedom from other communities especially the Tamils so as to be in an exclusive Sinhala Buddhist state. It is this freedom Sinhalese have sought in the united Sri Lanka.

The nature of the fascist totalitarian grip of chauvinist state over the Sinhala mindset is such, it has become impossible for them to engage honestly with the Tamil leadership or consider the accommodation of historical and self rule rights of Tamil people over their own territory. ‘Everything is ours’ has been the arrogant contention throughout. To achieve this Sinhalese would like to see all Tamils killed or banished from Sri Lanka. The desire of the Tamil people to share Sri Lanka has been turned into a cause of their annihilation.

Sometimes in the past the Sinhalese leaders expressed their chauvinist mission by declaring that there is no ethnic problem. This has now been extended as there are no minorities in Sri Lanka by which they express their desire that they would like to be all alone in Sri Lanka and would like to see all the Tamils killed off or banished from Sri Lanka. It is an existentialist issue. Can the Sinhala race idea survive outside the unifying mission of Sinhala chauvinism by which it hopes to take possession of all of Sri Lanka? If the answer is no, then separation is the rational solution for the ethnic problem in Sri Lanka.

The opportunity which parliamentary democracy provided for usurpation and pursuance of the chauvinist ideal at the expense and the abuse of the unitary pluralist ideal brought ruin to the Tamil people in Sri Lanka. The exclusion of Tamils from the state process by the implementation of the Sinhala Only Act, the Sinhalese communal violence against the innocent Tamils or the conspiracy to drive them out of the country by occupying an oppressing the Tamil areas has been important features of Sinhala chauvinist agenda. Through the exclusion from development and dishonouring agreements that would uphold the rights of Tamil people Bt advancing a genocidal programme against the Tamils in the name of fighting terrorism, the Sinhalese have taken the Chauvinist agenda to its near conclusion.

Finding peace in Sri Lanka has become compounded by issues of international concerns and schemes which cannot be entirely avoided. The past history of colonialism teaches, the holding on to the absolute ideal of taking possession of all of Sri Lanka, which violates the rights perception of vast chunks of Sri Lankan people and failure to resolve the ethnic problem will continue to be a cause for the gradual decline of an independent sovereign nation and its eventual demise. Due to her strategic placement, Sri Lanka will always be converted by powerful external forces. Past experience should be a lesson for choosing to exploit these external forces for local political gain and play into their schemes.

Buddhism in Sri Lanka went into decline and ruin many times in the history. It declined with the decline of Anuradhapura civilisation in the first century which was mainly due to natural calamities. It revived again in Anuradhapura after a few centuries to decline again by the 6th century, it saw another decline until its revival in Polonaruwa in the 13th century. This again saw the end with the overrunning of Polonaruwa by Kalinga Mahan and Hinduism rose to pre-eminence with emergence of Kingdom of Jaffna. The last of banishment of Buddhism came in the period of Sitahwaka Rajasinga I in the 17th century after which Buddhism completely disappeared from the scene. Every time Buddhism went into ruin, as in India, the main cause of its decline and demise has been its own unsustainability and its rejection by the people and the burden it imposes on the state.

The decline of Hinduism, which is the historical religion of Sri Lanka, came not from Buddhism but from the Portuguese who first arrived in Sri Lanka in 1515 and established a firm foothold by 1530 and who like the Buddhism of today, dreamt of converting the whole of Sri Lanka into a Catholic country. The Portuguese systematically went about destroying all the well endowed Hindu temples that stood throughout the length and breadth of the country and converting the people into Catholicism. This continued until their expulsion from the island in 1658. The Dutch who followed them were mainly concerned with banishing the Portuguese and the ‘popish gang’ as they called the catholic priests, and prosecuted the Catholics, though did not forcefully engage in conversions to their religion of Calvinist Christianity, during which time Hinduism recovered but never to its original glory.

Though King Kirthsiri reintroduced the Siamese sects in middle of 18th century, the opportunity for its further revival came in the 19th and 20th century after the success of Kandyan Conspiracy in 1815, which ended the Hindu sovereignty of Sri Lanka when the opportunity for the revival of Yellow Buddhism ( Siamese sects among the higher casts and Burmese sects among the lower casts ) became possible. This has been taken to new height in the independent Sri Lanka. The revival of new variant Buddhism called ‘Sinhala Buddhism’ which never existed in history, intensely linking the two ideas with a claim for the whole of Sri Lanka based on the prevalence of Buddhist ruins and imaginative historical misrepresentation in a way that never existed in Sri Lanka .

However, Hinduism never in history of Sri Lanka went into ruin and both version of Hinduism, the agamic Brahminical version as well as non Brahminical Dravidian version have remained vibrant throughout the history of Sri Lanka. Both Tamil people and Sinhalese people have followed the two versions without any difficulty and they continue to do so to this day. Almost all the sovereigns of Sri Lanka has been Hindus, though occasionally they supported Buddhism. Very often they took stern action against Buddhist sects when their actions became detrimental to the exercise of sovereignty over Sri Lanka and their institutions unsustainable.

As Tamil people in the North East were not under any Sinhalese rule at any time in history except in the world of historical concoction and misrepresentation and the period before the arrival of the Portuguese in the 16th century, the whole of Sri Lanka has been under the Tamil rule for nearly three century, the reassertion of Tamil sovereignty was a historical imperative in an independent Sri Lanka. This became more important in the face of the emergence of chauvinist Sinhala Buddhist national ethos as a unifying ideology of the Sinhala race in the independent Sri Lanka. Without providing for the freedom and opportunity for the articulation of the free will of two people within the framework of a united Sri Lanka, a peaceful, sustainable Sri Lanka that can progress without further facing disintegration and subjugation is not possible.

Te resurgence of the Sinhala nation at the expense of a plural Sri Lankan with the opportunity for majoritarian usurpation was predetermined. The opportunity for it revival was enabled by the democratic process with all its flimsy projections into the historical past and racial reorientation as Aryan Sinhala Buddhist, that saw the antagonism between the two communities multiply many fold in the independent Sri Lanka, in a way that never existed earlier periods. As the state process and the constitution remains subordinated the chauvinist agenda that threatens the very existences of the Tamils, providing for the self preservation and national well being and coexistence of the Tamil nationhood and Sinhala nationhood within one nation has become inescapable reality.

The idea of plural society and the Sinhala Buddhist state are incompatible. The projection and promotion of a Sinhala Buddhist state has been a national obsession of the Sinhala race in the independent Sri Lanka. Starting from individual Sinhalese to institutions and all the Sinhalese political parties subscribe to it and are under the siege of the chauvinist mission. The mindset disposition and orientation of the Sinhala race and its institutions cannot be dismantled in favour of the plural idea any more. Attempts to coax the plural unitary state over Sinhala Buddhist unitary state is akin to pulling up the trousers on shit. Without trying to deceive and dupe ourselves, what has to be faced is the reality that the unitary state in Sri Lanka will be a Sinhala chauvinist state and a solution has to be found for the unity of Sri Lanka outsider the idea of Sinhala chauvinist unitary state.

Though united Sri Lanka remains a rational idea raising emotions in the minds of perhaps everyone, let these passions and emotions not blind the contours of reality and rationality. Global barbarism and yellow imperialism would like to see Sri Lanka turned into its outpost and would like to occupy Trincomalee at the earliest. But the way forward for this is not through killing off all the Tamils or agreeing to mutilate the Tamil homeland to be on the good books of Sinhala chauvinists in order to take possession of Trincomalee. The genocide of Tamils in Sri Lanka which started with the arrival of the Portuguese in the 16th century, has continued to this day. Only a political arrangement that enables the Tamil people to care for themselves can end this.